A Conversation w/George Wein

““Jews by nature, throughout history, were forced to be entrepreneurs. They had to think for themselves how to make a living, because they couldn’t work in the big corporations or the equivalent. They had to work for themselves.””

National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master, George Wein, born on October 3rd, 1925, is considered to be as much a legend as his festivals. Through his company, Festival Productions, he has spearheaded hundreds of music events since 1954 when he produced the first Newport Jazz Festival – an event which started the festival era. Five years later, Wein and folk icon Pete Seeger founded the Newport Folk Festival. In 1970, Wein founded the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. He pioneered the idea of sponsor association with music events, beginning with The Schlitz Salute to Jazz and the Kool Jazz Festival. His company went on to produce titled events for JVC, Mellon Bank, Verizon, Essence, Ben & Jerry’s and others.

Joe Alterman: From Dylan & Me by Louis Kemp: Supporting the underdog is virtually second nature to Jews because we have so often been in that position ourselves. We seem to have a sixth sense when it comes to persecution, discrimination, and injustice, and many of us have devoted our lives to battling these things. There’s no question in my mind that Bob’s drive to write songs that mattered was born at least in part from his roots as a Jew.

I frequently read and hear speculative things like this when talking about Jews in music. You’ve done many things in your life and, if anyone speculated similarly about you, would there be any truth to the statement?

George Wein: I can’t speak to the Dylan quote, but the answer to your question is very real because Jews by nature, throughout history, were forced to be entrepreneurs. They had to think for themselves how to make a living, because they couldn't work in the big corporations or the equivalent. They had to work for themselves. So by nature, you'll find that a lot kids like yourself... I mean, you're a Jewish kid, and you're thinking for yourself, because 300 years ago, you would have had no alternative. You had to open up a shop, or you had to do something. Certain ethnic groups have characteristics. The Irish come to America, they have to take over city hall and the police department and the fire department. The civic thing. They have to take that over, that's their way of survival, because they were prejudiced against when they came here. They couldn't get... the banks. That's the answer to your question I think but whether that's drove me, I don't know. I always thought for myself. I never had a job in my life.

JA: I talked to a lot of Jewish musicians and people who love music, and they say growing up listening to jazz they kind of felt like they were related somehow to the musicians they were listening to. Does that make sense or did you ever feel like that?

GW: Well that's the second part of the question. I think the first part is doing something for yourself, and sometimes the arts are very attractive. And since, again, in Russia if you played the violin or played in the symphony orchestra they wouldn't take you in the army. So a lot of mothers and fathers made their children musicians, so they would not go in the Russian army, which was a sure death sentence. So everything historically does have a position. You wonder why there were so many violinists like Jascha Heifetz. They all came from the same area of Russia. Historically would get into that. Eastern European Jews were attracted to the arts. And that broadened all the arts that are available in a country like America in the 20 and 21st century.

JA: So if anything you did had to do with your being Jewish, it was more subconscious?

GW: Consciously no. I never did anything consciously that I was Jewish. In fact, if anything, the opposite. I mean it’s I have...You're aware of anti-Semitism. I don't know whether you run into it at your age, but I ran into it plenty at my age, in my era. I grew up where I was afraid to go to school because the kids were calling me “the f***ing kike,” and things like that. But once you got over that, you didn't give a damn, and you just were your own man.

I remember when I took my mother and father to Europe and went to the great museums. Of course, all the great musicians are all about renaissance painters which are all about Jesus Christ. And that’s the way they looked at the paintings. They looked at it as Jews looking at Jesus Christ. I didn’t do that. I looked at it as great art, and never thought for a minute that it had to do with the fact that it was Jesus Christ. That’s just the way I was. When my mother…and they’re talking about it, I had never thought like that.

I’m listening to them talk to each other and I'm showing them a great Botticelli or Raphael. They were looking at it as being Jews. I didn't look at anything as being a Jew. Again, I'm conscious of being Jewish. I'm proud of being Jewish but beyond that, no I don't meet people...

A lot of Jews are very, very self-conscious about being Jewish, very much so. A friend of mine who’s Jewish and on my board in Newport asks me, "Do they know you're Jewish?"

I says, "Why you ask me such a question?" I mean she was a wonderful person, a very bright person but she had this feeling. So I mean there's...So, no, I have never looked at things from that point of view.

Remember I married an African American girl. I didn't look at myself as a mixed marriage. I mean I change the story now. Mixed marriage is now between a man and a woman. That's a mixed marriage. In my days, a mixed marriage was between African American and white. It's changed. It's not a mixed marriage.

I never care about people. I never think about who they are, except in helping to deal with them. You know certain people have certain concerns or feelings or prejudices or something. And you want to know if the people you are talking to fit into them, so you search on them. I never thought of people when I hired them, were they Jewish or were they Catholic or were they... I never thought of people when I was dealing them.

I had a contract with a major American company and I made quite a bit of money. But then that contract was over and my partner at that time was Italian. He said to me, "Did you ever feel any anti-Semitism from those people you were doing business with?" I said, “No, anti-semitism is everywhere but I didn't feel it. I says "Why do you ask?" He says, "They would talk about giving all that money to that Jew in New York."

But it didn't bother me. They were nice enough to me when we were doing business, but in the back of their head, that was what they were thinking. I wasn't thinking that it was nice to get all this money from these Goys.

JA: I read this quote from Nat Hentoff, and he said that he felt like when he heard Benny Goodman’s “And the Angels Sing" and its "joyous, swinging, Klezmer-like Yiddish trumpet solo," he felt like he had been “welcomed into the jazz family." Do you ever hear…

GW: He was playing a Kosotzka (?), and it's [singing the melody]…I mean, that was "And the Angels Sing." Ziggy Ellman [the trumpet player who took that solo referred to by Hentoff] was very Jewish. If you saw his face, I mean, he looked like out of the bible. Ziggy Ellman was a great trumpet player, and Benny let him do his thing.

Nat Hentoff was a writer. He thought that was a nice expression that you welcomed him in the jazz family.

JA: Do you have a definition for Jewish music?

GW: Well, Cole Porter…you know that classic story? People ask him, "What is your formula for writing successful music for Broadway shows?

““I grew up where I was afraid to go to school because the kids were calling me ‘the f***ing kike,’ and things like that. But once you got over that, you didn’t give a damn, and you just were your own man.””

[Porter’s answer:] ’Write Jewish music.’

I mean, so when he used to do “What Is This Thing Called Love”, it resolves into a minor key, not to a major key. [signing] What is this thing called love…, becomes the Jewish music. “Like, My Heart Belongs to Daddy,” it's [singing]. So, he wrote a lot of songs that were minor, kosotzka (?) feeling. And he said it’s because the Jewish audience in New York responds to the music even though they don't think of it as being Jewish music.

JA: So, for you, it’s the major, minor thing...When you say his music was Jewish music, it’s Jewish in that he had that in mind when he was writing the song, even though he himself wasn’t Jewish?

GW: Yeah. He had that in mind when he was writing the songs, because Porter did. That's in his books.

JA: Would you think that anything in Hebrew is Jewish music automatically?

GW: Well there's a... Since I don't know much about Hebrew... I mean, I remember doing, when I went to Sunday School, ”Am Yisrael Chai”, if you remember that song.

But I mean, there were a few songs like that. But there's that great song about “My Yiddishe Momme” [singing]. I mean, that's Jewish music. That's the great story about the guy's working, his mother comes and says, "Sammy, can I get you something?" He says, "No, Ma, I'm fine when I'm working." Mother comes back in a half an hour, "Now, Sammy you should get something." "Ma, I told you, I'm okay. I'm working." Half an hour later she says, "Sammy, I'm worried about you." "Ma, for crying out loud, I told you to leave me alone," because he's getting madder, and madder. Finally, he gets up, he calls his partner, said, "I just thought of the greatest song." "What's the song?" "My Yiddishe Momme.” [laughing] It's a great story.

JA: Have you heard Billie Holiday's version of that song?

GW: No. I don't ever recall her singing that song. Was it “My Yiddishe Momme"? Or was it the French version? That was a French song you know.

JA: It was “My Yiddishe Momme.”

GW: I never heard it. She could sing the hell out of it.

JA: Oh yeah. I hear a lot of similarities between what she does and really good cantorial music.

GW: Well, I did a concert once where I had... It was one of the great thoughts in my life. Didn't work, but... I had the concert open with a blues singer in a spotlight. Karen Smith [?]. And I got the best Cantor in Brooklyn to come play for it. So, I opened the show and I had this all set in my mind. But we hadn't sold out the house. It was in Lincoln Center, called Monte Carlo. Opened up and the spot light's on Karen singing the blues. I'm waiting... The people all got up and rushed down to fill the seats. So the quietness I was looking for, and the harmony disappeared, and the whole beauty of what I was trying present, because the people were rushing to get close to the stage because the seats were empty. I was furious.

Then I had a Kosotzka band, and I wanted them to play. I didn't tell them what to do. I just hired them for what they... They decided they were just going to try to play jazz. [rolls eyes]

I didn't produce the show well enough. But I did the same thing - went to Chicago, blues. While the blues and the cantorial music can be compared, they really are not that close.

JA: I found this quote of Ornette Coleman. Talking about the first time he listened to cantorial music. He said, "I was in Chicago. A young man said I'd like you to come by so I can play something for you." I went down to his basement and he put on Josef Rosenblatt, and I started crying like a baby. The record he had was crying, singing and playing all in the same breath. I said, "Wait a minute. You can't find those notes. Those are not notes. They don't exist. Its more about finding the truth, than the precision."

GW: Cantorial music is very beautiful. To this day I hear it, and it hits you where you feel it. But I don't think of that when I hear the blues. I'll play the blues and sing the blues. That doesn't cross my mind. But I did try to produce a concert once. Just didn't do a good job.

JA: What was the stimulus for putting that concert on? Was it because you heard the similarities between the two?

GW: I wanted to create the similarities between the two. I wanted people to at least think about it. But I mean, there were different kinds of blues singers too, that play with an old sloy of cantorial music. There's New Orleans singers that...You get real folk blues singers. They don't sing in any notes that you know of. You can't find a key that they're singing in.

JA: Did you feel a bond with the other Jewish people you worked with because of y’all’s being Jewish?

GW: No.

JA: Nothing?

GW: No. I mean, I was proud that so many...There's a relationship in the arts because the same thing. It's a way I could earn a living. In the roots of the music, the blues that goes back to the plantation days were the same thing. It was in the soul of the people the way cantorial music is in the soul of Jewish people. If you grew up Jewish, and you went to Yom Kippur, you never forget it. It's part of your life. It doesn't mean you're thinking about being Jewish all the time. That's in your soul, and you're hearing it different from how the Gentile is hearing it. They're listening to it intellectually. You're listening to it emotionally.

You'll find that there were Jews, the Sephardi Jews, historically, doesn't mean individually, they're not quite the same feeling as the Ashkenazim Jews. Slightly different feeling, because they come from a different background, different culture. It's more related to the Muslim culture. It preceded the Muslim culture. Muslim culture is more related to the Sephardi culture.

““If you grew up Jewish, and you went to Yom Kippur, you never forget it. It’s part of your life. It doesn’t mean you’re thinking about being Jewish all the time. That’s in your soul, and you’re hearing it different from how the Gentile is hearing it. They’re listening to it intellectually. You’re listening to it emotionally.””

I was aware that Benny Goodman was Jewish and a lot of the white musicians were Jewish. Back then, a lot of them were Italian, too, because Italy has such a history. And Harry James was Italian. When he played “Cirbirbin," his Italian roots were coming out in that. A lot of musicians were Italian. Half the band, Benny's band…Toots Mondello…were Italian. So you can tie in a relationship of the music in the Italian culture. That's why most the better white musicians were either Italian or Jewish. Gerry Mulligan was an exception. He was Irish in roots, which have a different musical root.

JA: I was also curious about the Jewish/black bond. Did you know Mezz Mezzrow?

GW: Yeah. I think he was Jewish.

JA: He was, and he said the highlight of his life was getting thrown in the black section of the jail he was thrown into. He made it seem like he felt like he was somewhere in between white and black. I don't know if that…

GW: He was in between. He was high all the time.

JA: Nothing to do with being Jewish?

GW: He was mess. Louie Armstrong's favorite connection for the best marijuana.

Louis Armstrong was very influenced by Jews. He had a Jewish family in New Orleans that had more or less adopted him, and helped him, and he talks about that. And he sings [singing] the “Russian Lullaby”. I have a tape of him singing that unaccompanied when I was interviewing him. And he was just singing that because he'd talk about this Jewish family. So that had a big influence on him. So you can trace things like that. You can read Louis' bio. He talks about the Jewish family, and I have it on tape, singing “Russian Lullaby" sitting at a desk.

JA: But you’d never talk to him about it? About you being Jewish?

GW: Well, only when I interviewed. He brought it up. I didn't ask him. He brought it up. He was talking about his youth, this Jewish family. He was talking to me because he knew I was Jewish, so he probably was more concerned with that and telling me than I was concerned...

JA: You also presented some Jewish comedians.

GW: They were all Jewish. Mort Sahl, Alan King, I did Myron Cohen, for crying out loud. Shelly Berman, Irwin Corey. They're all Jewish.

Jack Benny was Jewish. Eddie Cantor was Jewish. Fred Allen was not Jewish. He was the exception. Jewish humor was more of an influence in American comedy than Jazz.

But see the unfortunate days of ethnic humor are over. It's politically incorrect to tell Jewish stories, or Italian stories. Used to have the great characters, George Gibit, the greatest ambassador. The Marx Brothers with Chico.

JA: We did a little tribute to Chess Brothers on last year’s festival, and told that complicated Jewish/black story. It was pretty fascinating.

GW: That industry was a lot of Jewish. Well the music business, publishing business all have been involved with the Jewish influence.

JA: It's really interesting looking at something like Chess Records because you can't tell sometimes if they were being greedy, or if they were just having good business practices, or if they were... It's a tricky thing. I don't know if…

GW: There's nothing tricky about it. They didn't pay royalties because they needed the money. They wouldn't have stayed in business if they paid you royalties. All those small record companies... Because once they made a hit record, the artists were making more money than they were. The artists were out there making... Used to buy those groups for $600 a night, $800 a night, but the records were selling for 35 cents. Sell a thousand records, two thousand records, you had a hit, but you didn't have any money.

JA: So it wasn't a greed thing, it was staying in business?

GW: Well, it became a greed thing. It's a very touchy subject if you have friends...Did they have Muddy Waters on their label?

JA: Yeah.

GW: One of them [Chess Brothers] was in Nice, and Muddy was playing at the festival. They wouldn't come to the festival. They didn't want to see Muddy Waters.

I may have that wrong. I didn't know the Chess Brothers that well.

JA: Well, a lot of people just make the point that they preserved all this great music.

GW: Well they did. They did.

JA: I’m curious what you think of the following, from Ben Sidran’s “There Was A Fire: Jews, Music & The American Dream”?

The Jews preserved the roots of Black American Culture. These small, independent labels were responsible for preserving a huge spectrum of American Music from Thelonious Monk to Muddy Waters, and in the process helped elevate American street life to the realm of high art. And not just the manufacturing and marketing of this music was in Jewish hands. For example, bebop was difficult for many jazz fans to comprehend, but Jewish writers such as Leonard Feather, Nat Hentoff, Dan Morgenstern, Ira Gitler, and Nat Shapiro took up its cause explaining to the average fan why this music was important while symphony," he said, "similarly championed it cause.

GW: No, I mean it's true. What he's writing is true. But I don't think it was because they were Jewish.

JA: They all just happened to be Jewish?

GW: Yeah. That's a different story. But, as Jewish kids, they're going to be thinking of something all the time.

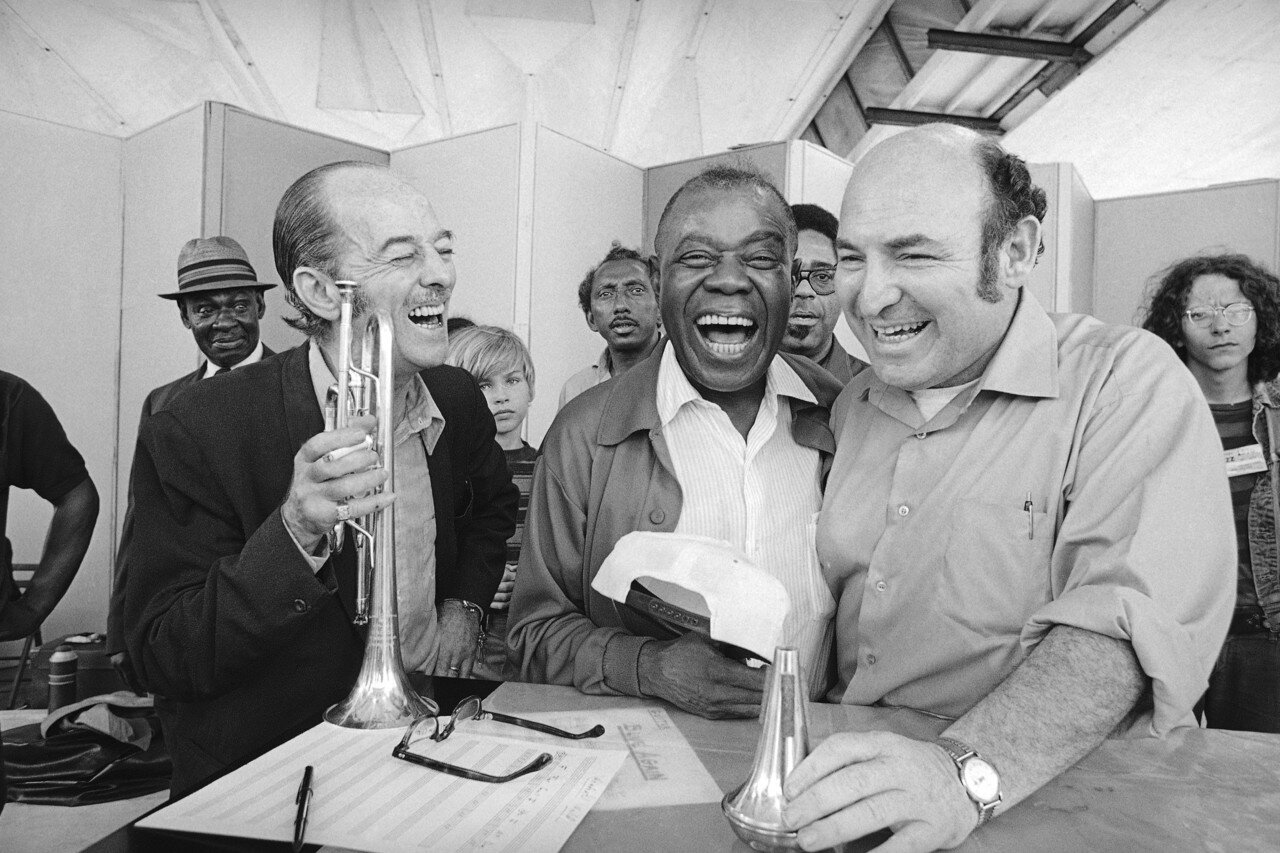

Above: George Wein with Louis Armstrong