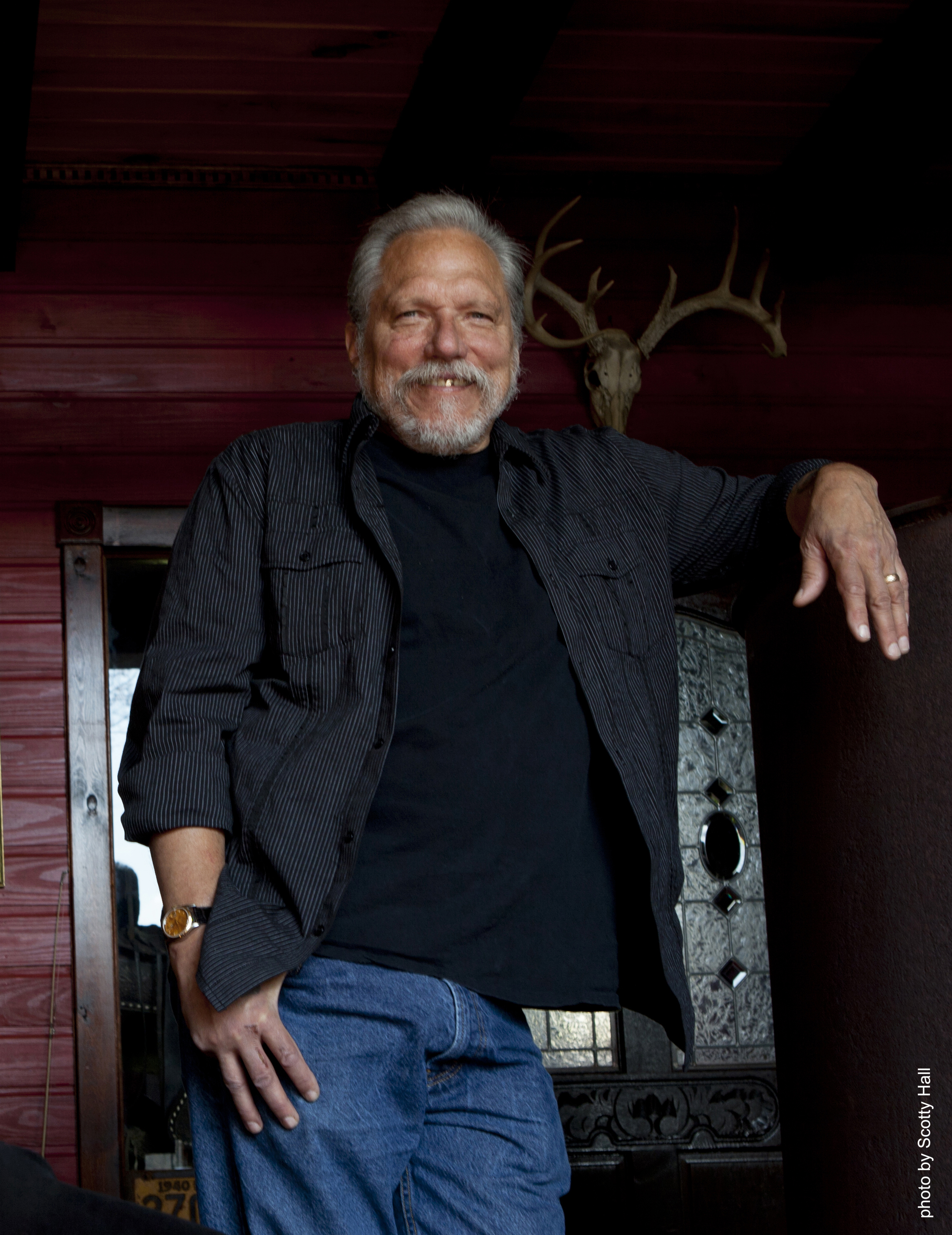

A Conversation with Jorma Kaukonen

““It took me years, I think, to identify the cultural significance of the different tastes of potato salad.””

In a career that has already spanned a half-century, Jorma Kaukonen has been one of the most highly respected interpreters of American roots music, blues, and Americana, and at the forefront of popular rock-and-roll. A member of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and a Grammy nominee, he is a founding member of two legendary bands, Jefferson Airplane and the still-touring Hot Tuna. Jorma Kaukonen’s repertoire goes far beyond his involvement creating psychedelic rock; he is a music legend and one of the finest singer-songwriters in music. In 2016, Jorma, Jack Casady and the other members of Jefferson Airplane were awarded The GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award for their contributions to American music.

Joe Alterman: A little background to inform our conversation: I'm 30 years old and the Executive Director of the Atlanta Jewish Music Festival, but until last year nearly my entire professional career has been as a jazz pianist, working with mentors like Les McCann and Ramsey Lewis. I've always identified as more of a cultural Jew, but the opportunity to run this festival came up and I was really drawn to it because of my fascination with Jewish contributions to the music, and I love the challenge of exploring the concept of defining Jewish music.

So, I thought it'd be interesting to start here: when I started this job, I attended a few local classes on Jewish music. At each, the teacher would stand at the front of the room and say "Billy Joel's Jewish", and then he’d play a Billy Joel song. He’d then move on to Bob Dylan. “He's Jewish”, he’d say, and then he’d play one of Dylan’s songs. Then he’d move on to Olivia Newton-John, doing the same thing. While the class members all seemed pretty into it, I was underwhelmed. Something felt missing to me…Is there anything Jewish about these people's art because they all happen to be born Jewish?

Jorma Kaukonen: It's an interesting thing. But first, speaking of Ramsey Lewis, you're definitely in with the in-crowd now…But anyway, this is a conversation that gets had periodically and I find it interesting on many levels because first of all, it's undeniably true that in the history of quote unquote popular American music…and I don't really know that much about jazz artist’s backgrounds…but it seems to me like there are more recognizably Jewish people in quote unquote popular music for whatever reason, I don't know. But you think about so much of this writing and so many of the melodies that came out of Eastern Europe, like "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" Yip Harburg wrote the lyrics to that. I mean, that sort of major/minor shift, I guess in a way, if you're looking for it, it reminds me of “Shalom Aleichem” on some level, you know? But again, I'm not from an observant Jewish family, so I don't have those blatant connections as a guy like Andy Statman would. But I think, and for whatever reason, undeniably it's there. I mean, think about Mike Bloomfield, the great blues guitar player. He’s undeniably Jewish - in many ways more Jewish than myself because I never got bar mitzvahed and he certainly did. In fact, I remember him talking about it: "I didn't have the blues! My dad is rich! I had a big Bar-Mitzvah!” You know?

““I mean, maybe that’s the most Jewish thing: supporting artists as opposed to blatant content. ””

But it's an interesting connection. I remember a couple of years ago, our rabbi…we go to a very, very liberal reconstruction congregation where our rabbi is not only a woman but she has a little tattoo on her ankle and her husband is a writer, teaches literature up at the University of Pittsburgh…and I got included on some white supremacist site visit out of Coeur d'Alene or one of those places up there where such people dwell, and there was a lot of us guys that are in the blues/rock world, et cetera. And I remember talking to my rabbi's husband about it and he laughed. He said, “Oh yeah, I remember.” And, in whatever the site - this is years ago - someone said we [Jews] were taking over the entertainment industry and my rabbi's husband said, “We took over the entertainment industry decades ago.” Now if they were talking about the Welders' Union, that'd be a different story.

JA: If you had been sitting in one of those classes, would you have thought anything was missing? Each class, the whole time, I’d be thinking, 'what's the Jewish part’?

JK: Well, that's a good question. And in our conversation, I guess the question always is what's the Jewish part? Aside from the fact that my grandmother who hung with Emma Goldman and did all these quasi-anarchistic things and whatnot, was certainly anti-establishment in a lot of ways, but she loved art and even though she didn't like the music that I got to do when I got into music, she supported my right to do it. I mean, maybe that's the most Jewish thing: supporting artists as opposed to blatant content.

I mean, that being said, if you get a chance to listen to my version of "Hesitation Blues", which is borrowed heavily from Reverend Gary Davis's version, that starts, it goes A minor, E major, A minor E major, A minor, E major, A minor to C seven, and now it’s in C major!

So reading the history of Reverend Davis, it's said that at some point he lived with a Jewish family somewhere in the Carolinas. I mean that kind of major/minor shift to me, I hear it. I'm not an expert on secular Jewish music by any stretch of the imagination, but I hear those kind of moves a lot. Maybe that's as good as it gets, I don't know.

JA: There's also a social justice component to "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?” that kind of made it a precursor to songs like Marvin Gaye’s "What's Going On”.

JK: True, that was true, that's also true. It was a social commentary and Yip and the guys almost got blacklisted. That song was considered un-American when it came out…But what would make it better for guy like that? Really?

JA: I read a lot about American Jews just wanting to be seen just as American. But, in most cases, they also wanted to hold on to the “other” thing. But, as Ben Sidran says [in There Was A Fire: Jews, Music & The American Dream] - and I’m paraphrasing - by being an outsider, he was kind of an insider, if that makes sense.

JK: Well, you know, that makes perfect sense to me too, because I'm a second-generation American and my mother's parents came over from Russia and my grandparents from Finland. And so here I am…on some level, especially growing up in the fifties like I did, where in the neighborhood where I grew up - as sort of a suburb of DC…in that era the outsiders were Jews. There was a synagogue in our neighborhood, B’nai Brith, and we weren't observant…that wasn't part of my life, but because we were considered Jewish by the other kids in the neighborhood, I got shit for it all the time. So I got the crap but none of the social armor, you know?

JA: So, what did it mean to you as a child to know that you were Jewish?

JK: I don't think I really realized at the time what the deal was. My maternal grandparents lived with us, or we lived with them most of the time…it was the second World War, my dad was away so we lived with my grandparents, etc, etc. And I realize…you know, DC is really a southern town…And so my best friend from elementary school through high school, his family was in a small town in Virginia called Tappahannock; it’s down on one of the tributaries of the bay down there. And there's no question that it's a deep south town in a lot of ways; if you saw that movie "Avalon" that came out, when all the families in this Baltimore town, they go to the beach, the black cars and stuff, the picnic stuff they did - that was my grandparents. Grandparents either had a black Buick or a black Packard and we went to the beach and they made all this stuff my grandmother made. Well, when I went down to visit my buddy Dylan in Tappahannock and his mother made potato salad, I remember saying, “this doesn't taste like potato salad I know”. Her feelings were hurt, and the reason was because I was eating deli food and the deli recipes because that's what my grandmother did. That was just my world, and it took me years, I think, to identify the cultural significance of the different tastes of potato salad.

JA: That's great. I'm really fascinated by how many searching, spiritual Jewish musicians don't connect with Judaism at a young age and find through music what they were led to believe they would find through Judaism, but then years later come back to it and kind of realize it's the same thing. For Sidran, for example, music at its best and a synagogue service at its best makes you feel connected to the past, which I love, and I’m curious how you would compare your musical journey to your Jewish journey?

JK: I like that too.

“I just felt comfortable surrounded by Jews. And I found that interesting because I’d never been consciously a part of a Jewish community before. And I really feel that to this day. We tend, in our family, only to go to high [holiday] services if it’s convenient. I mean, we’re sort of casually observant, but when we go, I really feel very comfortable there. And I think that dovetails in whatever journey my musical path has taken.”

Well, I've really consciously rediscovered my Jewish roots that were always undeniably there. And I think on some level, especially when I was in high school, I don't think I would've even known what an assimilationist was, though I'm sure that's what I was. Now, my wife converted to Judaism a decade and a half or so ago. And when she did that, I went to all the classes with her, and if I'd kept up with it, I could probably still read biblical Hebrew, but, of course you know how quickly that dissipates out…But what I discovered in the course of doing that was even though I'd never learned any of those things that so many of my Jewish friends at my age and younger ages too just grew up doing because they went to Hebrew school and stuff like that…so in spite of the steep learning curve that I needed to do to learn the Jewish alphabet and the Hebrew that I needed to do in order to quote unquote pass the class, I just felt comfortable surrounded by Jews. And I found that interesting because I'd never been consciously a part of a Jewish community before. And I really feel that to this day. We tend, in our family, only to go to high [holiday] services if it's convenient. I mean, we're sort of casually observant, but when we go, I really feel very comfortable there. And I think that dovetails in whatever journey my musical path has taken. I mean, when I started listening to music seriously - not just rock and roll, but the stuff before then and the stuff I went back to…folk music, whether it's a more sort of traditional quote unquote folk singer like a guy like Theodore Bikel, or a blues guy, like Big Bill Broonzy, there was that connection on some level. The social activism would bridge the gap between the musical genres, if that makes any sense whatsoever.

JA: Oh yeah, definitely. Some musicians who came back to Judaism later in life say that when they were younger they kind of felt intuitively like the musicians they were listening to were related to them in some way. Did you feel that with people like Reverend Gary Davis?

JK: Yes. That's really well put and I agree. Again, I'm not sure I would have intellectualized it in quite that way, but many of my friends like David Bromberg and my other buddies that are quote unquote Jewish Americana musicians, for some reason the music just made sense. It was so odd, especially Reverend Davis, 'cause so much of his stuff are spirituals, but it just made sense at the time. And I'm not quite sure why that is. I mean, I understand why the blues material made sense because the blues songs I got into as a kid were about true things. They were no longer about “cross over the bridge" or “how much is that doggy in the window". I mean they were things that if we couldn't absolutely relate to because we didn't grow up poor and black in some disenfranchised area of the United States, but they talked about, real love of real, real pain, real this, real that. It just seemed easy to relate to. And again, I'm not quite sure why this is, but I'm not the only person I know in this boat that's said that.

JA: With someone like David Bromberg, did the fact that you're both Jewish have anything to do with your deep musical bond? Do y’all talk about being Jewish?

JK: I got to know David back in the early eighties and I don't think we ever mentioned it once, except maybe in some humorous way to note here that we were Jewish middle class white guys playing blues.

Now one of the interesting things that has happened over the years is when I was a kid, way before that, and just starting out, the highest compliment you could get from any of your peers was that you sounded black. I mean it sounds absurd to say that today, but we said stuff like that and it meant something. I guess if there's any good news on the racial front of America today, it's that nobody would think to say that anymore.

JA: Do you feel a part of a great Jewish tradition in American music?

JK: I guess that I would only say I feel a part of that when we have one of these discussions, because it's not something that tends to surface in my mind, but it depends on who I'm with. If I'm hanging out with...again, you know, I wrote my autobiography a couple of years ago and our rabbi's husband was one of the guys who helps me edit it. And so we spent a lot of time talking. And when he and I talked about stuff, I absolutely felt a part of it.

JA: Really?

JK: Because then I was in that universe. The universe that I inhabit most of the time when I'm not home tends to be very secular and most of the time non-Jewish. Now I've got a tour coming up where I'm going to be doing a bunch of stuff with David Bromberg and I guarantee we're going to talk about it cause we always do.

JA: Is it more like, “let’s go get bagels”? Or is it talking about more spiritual kind of things?

JK: Yeah, well there's nothing like a good water bagel…But I think what we talk about more often than not is source, source material, where things come from, sometimes where the spiritual energy comes from, and that ongoing discussion about why is it there's so many guys like us who love this kind of music.

Now David, humorously one time - and I'm going to paraphrase him 'cause I would never seek to speak for David - he goes, ‘well maybe, maybe it's the slavery issue.’ And then I remember it cause we were at the ranch when he said that. Then he laughed and he said, ‘nah, back in the twenties the Jewish managers were ripping off the black guys.’

JA: I'm just curious, when I started this job, one of the things I did was try to define Jewish music. So I met with all these rabbis and basically I found out that everyone has a different definition for this. You know, one person said it's anything from Israel. I had heard some bands from Israel that had I not known they were from Israel, I’d've thought they're a Taylor Swift copy. People say the same thing about music in Hebrew and I found a band that things Johnny Cash tunes in Hebrew. Someone else said that, to him, it's anything based off the Old Testament, which, under that, makes a lot of black spirituals Jewish music. Do you have a definition for Jewish music?

““I remember the last time I was working in Israel, I spent some time at Tel Aviv on a day off and I got together with one of their Folk Blues Societies and they were playing American blues and singing in Hebrew. So I would have to say that that was Jewish music in that moment.””

JK: You know, I'm not sure. That's tough…I guess if I was pressed against a wall and said you have to come up with something, I would say Klezmer music. I don't think you'd deny that, but I remember the last time I was working in Israel, I spent some time at Tel Aviv on a day off and I got together with one of their Folk Blues Societies and they were playing American blues and singing in Hebrew. So I would have to say that that was Jewish music in that moment.

JA: Yeah. It's tricky. I mean, I've heard Klezmer music sometimes not being played by anyone Jewish. I don't know if that makes any difference…

JK: Yeah, I'm not sure either. In a way it's almost 'how many angels can dance on the head at the end of that’ kind of discussion, you know? But I think it's a valid question because it opens up an interesting dialogue. And I think the survey is in the eye or rather the ear of the listener and I would not take issue with any of the examples that you gave me. It just to me the only purely Jewish things that I can think of right off the top of my head, 'cause it has such a lineage of compositions in that genre, is Klezmer music.

JA: Was your spiritual journey a lot different than your Jewish journey? Would you say they were separate until fairly recently?

JK: I think I would have to say, looking back on it now, that in a way they were parallel, but when I be gained more of a Jewish awareness, it gave me a different context to look at things and I realized that I was on, in my opinion, certainly a Jewish path of discovery without using that language. I would probably use that language more today because I have that frame of reference now.

JA: Last question is kind of a silly one, but I have to ask. I was just curious if you've seen that scene from the Coen Brothers’ “A Furious Man” with the rabbi talking about Jefferson Airplane.

JK: Of course!

JA: What did you think of it?

JK: I loved it. Well, first of all, what's not to love and like about Coen Brothers film? But, especially the kids and stuff, those are the Jewish kids in my neighborhood. And like I said, I wasn't part of their social circle, but I've looked at them when...wow, that's like Chevy Chase, DC, 1953. And of course when the rabbi mispronounces my name and I mean, what's not to like about that?

JA: Anything else come to mind?

JK: No, it's been an interesting conversation. Listen, come on by after the show and we'll talk a little bit to see if you heard any Jewish music in our stuff.